“What?!

We couldn’t believe what we were hearing. This officer wanted our team of mentor-Marines to patrol the route with the record for the greatest number of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) ever found in our area of operations. On foot. At night. With Afghan military partners we had just met — partners who seemed an awful lot like the last set. That last set had attacked their mentor team, inflicting 25% casualties. Two were killed, including the lieutenant colonel leading the team. HQ sent me as a replacement, along with a major whom the deceased lieutenant colonel had intentionally reassigned away from the team. Now we were commanded by him, an officer none of us liked, respected, or trusted. And I was his second-in-command.

“Great!” quipped one of our lieutenants. “We’ll find the IEDs a way none of the Taliban would ever expect … with our legs!”

Luckily for everyone, this major was soon recalled to be investigated for misconduct. His last significant act before departing? Promoting me to captain, the senior officer on the team. Super.

The Universal Importance of Leadership

That “leader” failed. I’ve seen others fail, too, and have done some failing of my own. I’ve seen some leaders succeed beyond any reasonable expectation. This is true for both of my main areas of professional experience: the military and technology products. However, the leadership training we’re offered as Marine officers is among the best in the world, and the fire of experience in which we temper that training is hotter than most.

I spent the first eight years of my professional life leading operations and intelligence in the U.S. Marine Corps. Since then, I’ve led product management teams. Some of the techniques from one context can apply well to the other, and this series is an effort to outline when and how they can. (Read Parts One and Two of my series on the similarities between product management and the military if you’d like). Today’s topic, leadership, is universal.

Leaders are essential to the success of any goal. Leaders outline the vision and the mission to be done, guide and mentor teams, and demonstrate how to accomplish goals. Leadership is not an option — it’s a necessity. If you choose not to lead, someone else will. If you are unable to lead, someone else will. Finally, if you fail to lead well, someone else will, and you will no longer be the leader. There are four key attributes you can learn here that are essential for leaders in any context.

The Trinity of Leadership

There are three main elements of leadership, plus a tricky fourth element that gets many in trouble.

- Example. You must always set the example — this is completely non-optional. If you do not set the example, someone else will, and that person will now be the leader.

- Mission. You must articulate the mission, prioritize it, and explain the who, what, when, where, and (most crucially) the why! If you aren’t the one setting priorities, someone else is — that someone else is now the leader.

- Team. You must take care of your people. You must employ your people in accordance with their abilities, develop them, and look out for their welfare. If not they’ll find someone who will to lead them.

- Authority. You often need to be visible as a leader. If it isn’t apparent who is leading, things can become chaotic. But this is a deceptive and difficult element.

The Example

We all know that leader. This person is the one who’s in before anyone else every morning and stays till the last person leaves. The one who seems to know a little bit of every person’s job and pitches in on any task when needed. Who understands what motivates the people she leads and communicates with them clearly, in the ways they need. Who knows when a teammate needs a break or vacation and asks them to take it. That takes those herself, too. We all feel compelled to follow her whether she’s in a position of formal authority or not. She may not do everything, but she would never ask someone to do something that she would not do herself. She is leading by example.

The Mission

If someone is leading and people are following, then there must be something that needs to get done. A leader must share the “why” of any effort. The military inculcates leaders with the “5Ws” — who, what, when, where, and, most importantly, why. We’re trained to formally convey the “why” at least two levels up in organizational structure. Every member of the team understands the intent behind the mission and how it fits into the mission of the next level up, the adjacent teams, and even the level above that (e.g. a squad knows the platoon’s mission and the company’s too). This way, if communication becomes untenable and subordinate leaders (or anyone) needs to make a decision, they can. They are empowered to decide in a meaningful way because they understand the whole of the mission.

The Team’s Welfare

A leader must know the people on her team and look out for their welfare. She must employ them in accordance with their abilities. She must understand their motivations and needs and communicate with them clearly. A leader recognizes that she leads people only by their consent. If she can’t outline a mission worth achieving and demonstrate that she truly cares about her team, she will lose her place. People know when a leader cares about them and when a supervisor views them merely as a “resource.” She must invest in them, constantly develop their skills, and establish true rapport. A leader must love her team. When the time comes that a leader must ask for sacrifices, it is knowing that the leader loves them that allows teams to persevere.

One of the most successful recent technology-related turnaround stories relates directly to mission and teams. When Satya Nadella took the reins at Microsoft, he stepped into an organization where the mission arguably no longer applied. Team welfare was so neglected that cartoonists depicted the company as at war with itself. Many authors have written about the turn-around Nadella led by resetting Microsoft’s mission to “empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.” He did so because the former mission of “[a] PC in every home” had become obsolete. As he led the company into the cloud-based future with Azure, he simultaneously took care of his team. He required executives to read “Non-Violent Communication,” which helped remedy a culture of negativity and infighting. By changing Microsoft’s mission and taking care of his team, he lived up to his highly visible position.

The Authority

It can be important for people to know who is in charge so there aren’t competing missions. But the issue with being visible is that if you haven’t taken care of the previous three elements, you will lose your status as a leader very rapidly. The worst “leaders” are those with status and titles but without competence in mission, team or example. Some people mistakenly believe that having visibility and being seen as “in charge” will have a self-reinforcing effect. Sometimes, as my team experienced, someone will be handed a position. This can happen in the product world just as in the military. When it does, it can put the success of the mission and the team at risk. Teams can mitigate this risk by working to overcome gaps and relying on already-experienced leaders for assistance. This requires dedication, authenticity and the humility to work to improve yourself.

The Parable of the Hoplite

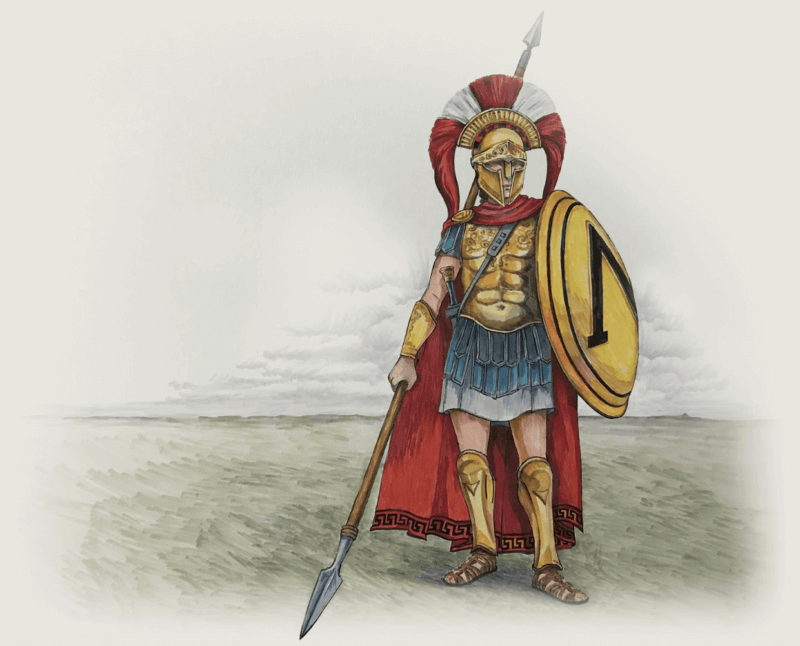

A hoplite was a heavily-armored Greek infantryman. In the story of the hoplite, we can discover a metaphor for the mandatory elements of leadership.

The hoplite carries a shield, a huge oaken plank with leather straps and bronze facing. This shield represents the team. It offers the hoplite protection but also protects his fellow soldier to his left. The hoplite carries a spear. It represents mission accomplishment. The whole reason the hoplite is here is to put that spear into the enemy. The shield is useful and protects him and his teammates. But without the spear, there is no point. Sometimes, the spear breaks and he must rely on his sword, but the intent of the mission continues. Other times, the shield is more important, and the hoplite and his fellow soldiers hold it high with their weapons at rest. Occasionally, they must accept risk and lower their shields, the spears working over the top of them and the mission taking priority. Usually, the hoplites seek to balance the two.

This hoplite is a platoon leader. His helmet carries a transverse (sideways) crest. This is so that his soldiers can pick him out in the chaos of the battlefield. When things are going wrong, they’ll look to him and know him instantly by his transverse crest. They will observe how his shield is dressed, protecting himself and his fellow soldier to his left. His fellow soldiers will observe how his spear is positioned overhand and doing the work they came here for. By looking to him, they will know what to do.

So, what feature of our hoplite represents setting the example we know is so critical? It’s his sandals. They’re not glamorous or flashy like the polished spearhead or bronze on the hoplon shield. They’re not eye-catching like the scarlet transverse crest. His sandals are dirty, sweat-soaked, and trampled flat in the dust. They are essential to the entire mission. If the hoplite loses his footing, none of his other assets matter.

What This Means for Leaders

This is true for all leaders. You must be the hoplite and all of his features. You need to take care of your people, protect them, and employ them in accordance with their abilities. You must have a purpose, a mission, to make it all worth it. Be visible, noticeable, and seen so your people can follow your example, take care of each other, and accomplish the mission.

Finally, you. must. set. the. example. You must be the hoplite and his sandals. Be willing to be dirty, sweat-soaked, tired, inglorious, and stepped on. Because the moment you’re not, you’ll lose everything else.